Zara's Fast Fashion Edge Businessweek Archive

Spanish retailer Zara has hit on a formula for supply concatenation success that works. By defying conventional wisdom, Zara can design and distribute a garment to marketplace in just 15 days. From Harvard Business organisation Review.

Editor's note: With some 650 stores in l countries, Spanish habiliment retailer Zara has hitting on a formula for supply chain success that works by defying conventional wisdom. This excerpt from a contempo Harvard Business Review profile zeros in on how Zara's supply chain communicates, allowing it to pattern, produce, and deliver a garment in fifteen days.

In Zara stores, customers can e'er discover new products—but they're in express supply. There is a sense of tantalizing exclusivity, since just a few items are on display even though stores are spacious (the average size is effectually ane,000 square meters). A customer thinks, "This green shirt fits me, and there is ane on the rack. If I don't buy it at present, I'll lose my take a chance."

Such a retail concept depends on the regular cosmos and rapid replenishment of modest batches of new goods. Zara's designers create approximately 40,000 new designs annually, from which 10,000 are selected for production. Some of them resemble the latest couture creations. But Zara often beats the high-fashion houses to the market and offers about the same products, made with less expensive fabric, at much lower prices. Since most garments come in five to vi colors and five to seven sizes, Zara's system has to deal with something in the realm of 300,000 new stock-keeping units (SKUs), on average, every year.

This "fast way" system depends on a constant substitution of information throughout every part of Zara'southward supply chain—from customers to store managers, from store managers to market specialists and designers, from designers to production staff, from buyers to subcontractors, from warehouse managers to distributors, and so on. Most companies insert layers of bureaucracy that can bog down advice between departments. But Zara's arrangement, operational procedures, performance measures, and even its part layouts are all designed to brand data transfer easy.

Zara'southward single, centralized design and production middle is attached to Inditex (Zara's parent company) headquarters in La Coruña. Information technology consists of 3 spacious halls—1 for women'southward vesture lines, 1 for men's, and one for children'southward. Unlike most companies, which endeavor to excise redundant labor to cut costs, Zara makes a point of running 3 parallel, but operationally distinct, product families. Accordingly, separate design, sales, and procurement and production-planning staffs are dedicated to each clothing line. A store may receive three different calls from La Coruña in one week from a market specialist in each channel; a factory making shirts may deal simultaneously with two Zara managers, one for men's shirts and another for children's shirts. Though it's more expensive to operate three channels, the information catamenia for each channel is fast, direct, and unencumbered by problems in other channels—making the overall supply concatenation more than responsive.

Zara's cadre of 200 designers sits correct in the midst of the production procedure.

In each hall, floor to ceiling windows overlooking the Spanish countryside reinforce a sense of cheery informality and openness. Unlike companies that sequester their blueprint staffs, Zara'southward core of 200 designers sits correct in the midst of the product process. Split among the three lines, these mostly twentysomething designers—hired because of their enthusiasm and talent, no prima donnas immune—work adjacent to the market place specialists and procurement and product planners. Big circular tables play host to impromptu meetings. Racks of the latest way magazines and catalogs fill the walls. A small paradigm shop has been fix in the corner of each hall, which encourages everyone to comment on new garments every bit they evolve.

The concrete and organizational proximity of the three groups increases both the speed and the quality of the blueprint process. Designers can speedily and informally check initial sketches with colleagues. Market specialists, who are in abiding bear on with store managers (and many of whom have been store managers themselves), provide quick feedback almost the expect of the new designs (style, color, cloth, then on) and advise possible market price points. Procurement and production planners make preliminary, but crucial, estimates of manufacturing costs and available capacity. The cross-functional teams can examine prototypes in the hall, choose a design, and commit resources for its production and introduction in a few hours, if necessary.

Zara is conscientious about the way it deploys the latest information technology tools to facilitate these breezy exchanges. Customized handheld computers support the connexion between the retail stores and La Coruña. These PDAs augment regular (oftentimes weekly) phone conversations between the store managers and the market specialists assigned to them. Through the PDAs and telephone conversations, stores transmit all kinds of information to La Coruña—such difficult data as orders and sales trends and such soft data as client reactions and the "buzz" effectually a new style. While any visitor can utilize PDAs to communicate, Zara's flat organization ensures that important conversations don't fall through the bureaucratic cracks.

Once the team selects a epitome for production, the designers refine colors and textures on a calculator-aided design system. If the item is to be fabricated in one of Zara's factories, they transmit the specs directly to the relevant cutting machines and other systems in that factory. Bar codes track the cut pieces as they are converted into garments through the various steps involved in production (including sewing operations usually washed by subcontractors), distribution, and delivery to the stores, where the communication cycle began.

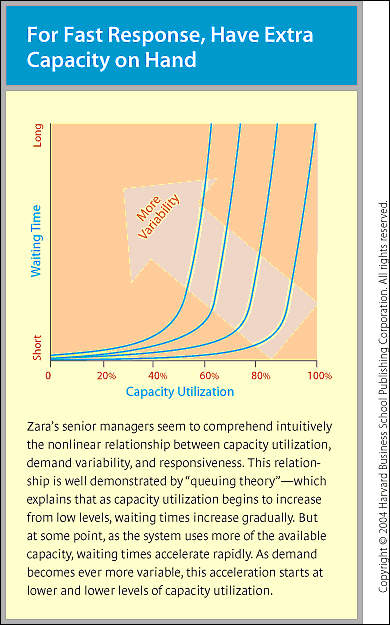

The constant flow of updated information mitigates the so-called bullwhip effect—the tendency of supply bondage (and all open-loop data systems) to dilate small disturbances. A minor alter in retail orders, for instance, tin upshot in wide fluctuations in factory orders later on it's transmitted through wholesalers and distributors. In an manufacture that traditionally allows retailers to modify a maximum of twenty percent of their orders once the season has started, Zara lets them adjust xl pct to l percent. In this way, Zara avoids costly overproduction and the subsequent sales and discounting prevalent in the industry.

The relentless introduction of new products in small quantities, ironically, reduces the usual costs associated with running out of any particular item. Indeed, Zara makes a virtue of stock-outs. Empty racks don't drive customers to other stores because shoppers e'er have new things to choose from. Being out of stock in one item helps sell another, since people are oftentimes happy to snatch what they can. In fact, Zara has an informal policy of moving unsold items later on two or three weeks. This can be an expensive do for a typical store, just since Zara stores receive small shipments and carry little inventory, the risks are small-scale; unsold items account for less than x percent of stock, compared with the industry average of 17 pct to 20 percent. Furthermore, new trade displayed in limited quantities and the short window of opportunity for purchasing items motivate people to visit Zara's shops more oft than they might other stores. Consumers in central London, for example, visit the average store four times annually, but Zara's customers visit its shops an boilerplate of 17 times a year. The loftier traffic in the stores circumvents the need for advertising: Zara devotes just 0.3 percent of its sales on ads, far less than the 3 percent to 4 pct its rivals spend. ![]()

[ Gild the full article ]

| |

Excerpted with permission from "Rapid-Fire Fulfillment," Harvard Business Review, Vol. 82, No.11, November 2004.

0 Response to "Zara's Fast Fashion Edge Businessweek Archive"

Post a Comment